Why unplugging from work is more work than we think

Unplugging from work: most of us probably think we do it—maybe we believe we’re pretty good at it. During our personal time we tuck our phones away and turn off our notifications. Maybe we’re even disciplined enough to not send an email during off-hours. A whole economy has sprung up, from digital detox camps for adults to gatekeeping apps to control our screen time, to help us detach.

And yet—sorry, hang on, did you hear that ding?—we’re still distractedly glancing at our phones, habitually monitoring inboxes and that ever-growing volume of work email, anticipating notifications even when they’re muzzled, and inadvertently missing the winning point at our kid’s ball game (shoot, sorry sweetie).

We agree that unplugging is important, but many of us aren’t succeeding at it—and it’s hurting us, our colleagues, and our companies.

A study by LinkedIn found that 70 percent of professionals don’t fully unplug from work. A recent study of 1,400 information workers commissioned by Microsoft found that 40 percent of people work outside of regular hours in a way that interferes with family time. And research from Utah State University found that a person’s use of their mobile device for work during family time not only negatively impacted the employee and their spouse, but led to higher instances of burnout, a decreased commitment to their employer, and an increased likelihood of quitting.

Even official vacation time isn’t sacred: 67 percent of the people surveyed by LinkedIn said they would go ahead and contact a colleague about work-related matters while the colleague is on vacation.

Despite these statistics, leaders are increasingly aware that to be successful, companies must help employees feel balanced. And frazzled, distracted employees are increasingly desperate to disconnect from the very work tools they’ve come to rely on so they can truly recharge.

“Ironically, we have found that in modern life the source of a lot of our stress and tension is software, the way it is structured to be very notification-centric versus human-centric,” says Kamal Janardhan, partner director of product for Microsoft Workplace Analytics and MyAnalytics, tools that harness data to help drive change in the workplace. “Unplugging is almost a defense mechanism against that system.”

Ultimately, the actions we take individually—putting our phones in a box, locking apps, setting nebulous rules for ourselves that we then try to cheat—are reactions, and they aren’t enough to solve a larger problem. We need to change the system.

New research and our growing understanding about human behavior tell us two things for certain: that unplugging is more necessary than ever, and that true unplugging is not a single action but a social agreement—a culture shift that employees and companies must create together.

Finding hidden culprits

To understand where we are headed when it comes to the intersection of work and personal time, it’s important to remember how we got here. Much of what we believe about how we should work harkens back to the industrial revolution and the switch from a much longer workday to a 40-hour workweek and a collective expectation to clock in and clock out at set hours. In the 21st century this belief system became ripe for reinvention again, but not necessarily in the ways we’ve seen.

You need to regenerate your energy. Unplugging is an emotional recharge that we all need.

With modern technology, handheld and wearable devices, AI, and the cloud, work and personal time have blurred together for knowledge workers, the boundary now often invisible. There is no clear punch-out time anymore.

“Companies and experiments have shown that if you shorten the work week, employees become more productive, creative, and loyal. Henry Ford understood this impact on productivity when he shortened the week from 60 to 40 hours,” says Kate Nowak, solution design lead for Workplace Analytics, which enables companies to understand how employees work and collaborate every day and to build empowered workplace cultures.

Changes in technology can empower us to evolve how we work, Nowak said. “We need more companies to step up and experiment with new ways of working to inspire broader change.”

At the same time, humans are still humans, and while technology and work styles have shifted rapidly, our circadian rhythms still control our patterns of focus and rest, says Mary Czerwinski, principal research for Microsoft, who studies worker interaction techniques and multitasking. We aren’t built to be in a constant state of “on.” Workers have natural fluctuations of energy and attention in their day, from focused work to rote work to boredom, and we experience two peak focus times—midmorning and midafternoon.

“As your circadian rhythm goes down, the negative effects of trying to focus start to go up. You need that natural homeostasis boost again. That’s why we go home and take a break,” Czerwinski says. “You need to regenerate your energy. Unplugging is an emotional recharge that we all need.”

Often, though, the ways we’ve tried to address overload and enable unplugging have backfired. Have you ever pledged to unplug more, maybe spurred by something like National Day of Unplugging, or your partner or kids giving you the stink eye? Have you created rules for yourself only to find within a few days or a week you are reverting to old habits, sneaking glances at your inbox, reaching for your phone without even consciously choosing to?

One key reason it’s so hard to unplug is something called anticipatory stress: the anxiety we feel worrying about something that is coming or could come.

It works like this: It’s Saturday night and you’re getting ready to head out to a nice dinner with friends, when you get a ping from your boss with a head’s up about an important early Monday morning meeting, more details to come. Suddenly, even though you don’t log on to do any work, you’re anxious, thinking about prepping for the unexpected meeting and checking your phone for more emails. Your mind isn’t on the meal and the good company and your weekend wellbeing, it’s hung up on what work thing might come next.

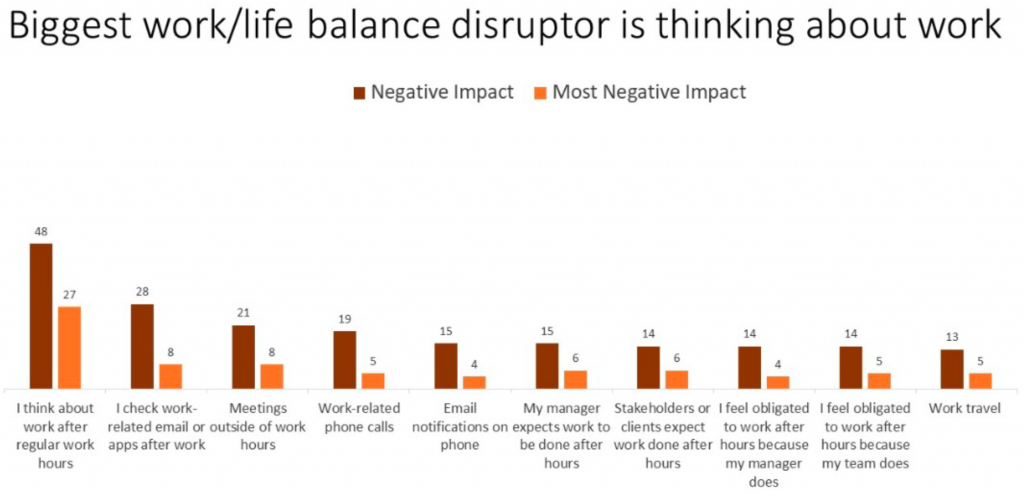

According to the recent study of 1,400 workers, nearly half of respondents said that thinking about work outside of work hours regularly has a negative impact on their work-life balance. And thinking about work during personal time was the biggest work-life balance disruptor, beating out other factors such as phone notifications, manager and client expectations, and pressure from coworkers who work outside of work hours.

Another recent study supports this, finding employees and their families experience the strain of expectation even if the employee doesn’t actually engage in work in their off hours.

Another reason it’s hard to change the way we work on our own is because behavioral change spreads in part by social confirmation—the more others adopt a behavior, the easier it becomes for each of us to do so, too. If no one feels like the company culture allows for true unplugging, few people will do it. Employees can’t go it alone.

At the same time, our strategies to address overwhelm often just lead to more work. Even Merlin Mann, the creator of Inbox Zero, backed away from his methodology eventually.

“Since greater efficiency has led to more work not less, what we really need are ways to protect ourselves from work expanding into the time we create for ourselves,” Nowak says.

And while many company leaders have embraced the goal of nurturing employee engagement and wellbeing through culture, the truth is that often, the pressure on workers to stay plugged in afterhours stems from hidden factors leaders might not even be aware of.

Using Workplace Analytics to analyze anonymized and aggregated digital signals from meetings, email, HR surveys, and other data sources, many Microsoft customers have looked at the behaviors of their workforce. Some consistent patterns connected directly to unplugging and work-life balance have emerged.

In one Fortune 100 technology company, for example, data revealed that every hour people managers spent working after-hours translated to 20 minutes of after-hour work time for direct reports. The numbers vary, but similar patterns have surfaced at several other companies.

In another instance here at Microsoft, leaders applied Workplace Analytics and were able to uncover the cause of a poor work-life balance rating by a group of engineers on an annual survey. It turned out that bloated, redundant meetings were keeping engineers from focus time during their day, so they felt compelled to finish work at home and couldn’t unplug. Compounding the problem, managers spurred afterhours email by leading by example. Once leaders gained these organizational insights, they kicked off a change program that worked.

Often, leaders can’t see the overall pattern of these types of behaviors or measure their true impact across a company. Through organizational analysis, company-specific insights emerge and leaders can work to evolve their culture, empowering employees to change collectively so they don’t have to go it alone.

Achieving personal balance

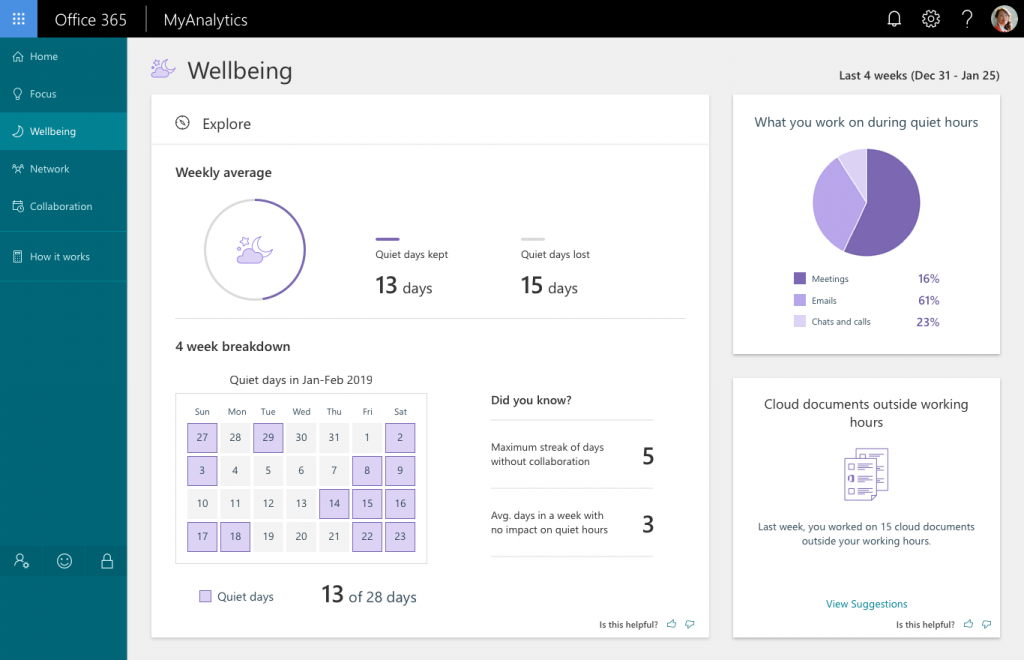

Designing another Microsoft tool that helps address work-life balance and the ability to unplug, this one driven from the employee side, product managers have recently shifted how they think about unplugging from work and employee wellbeing. Instead of telling employees how much time they spend working after hours every day, MyAnalytics—which shows personalized work metrics and insights only to individual employees—has changed to now track “quiet days” instead. An employee can look at their email digest and dashboard to see how many consecutive days out of their past month were quiet days—days without any emails, meetings, and chats outside working hours.

For instance, I can see that during a recent month my longest streak was 5 consecutive quiet days (including weekends). And I can see that 13 days of the month were quiet while 15 were not. By understanding work habits through this lens, I can mentally contextualize how impacted my personal life is overall by my work.

This new way of thinking reflects the research around anticipatory stress, says Wendy Guo, Microsoft senior program manager. When the MyAnalytics tool previously calculated after-hours work by the daily minute, many employees saw that, technically, they weren’t logging much time—maybe 15 or 45 minutes for instance. That might seem like maybe nothing to worry about—what’s 30 minutes a night sending emails, right?

But that measurement, and, more broadly, that way of thinking—day by day, hour by hour—doesn’t capture the cumulative stress of having your unplugged time constantly nibbled away at.

“It’s the pain of grazing,” Guo says. “Even if it’s 10 minutes checking email, scanning notifications, reading but not responding—it impedes your ability to mentally recharge. There is concrete evidence that people are engaging despite not wanting to.”

By reframing for employees how this accumulates, in a private, personalized report, Guo says her team hopes to empower workers with a sense of urgency “to think about work-life harmony, happiness, the things you can do instead of work when you allow yourself the time. To think about how you want to live. It’s ephemeral and not easy to quantify a sense of wellbeing, so we’re trying to help.”

With insight comes the power to evolve how we work so we’re productive and balanced in ways that work best for us. Just ask Vincent Fily, a global blackbelt seller in Microsoft’s Modern Workplace Sales division. Fily helps companies transform with tools like Workplace Analytics and the sister solution for employees, My Analytics. But when he moved back to France from the U.S. four years ago, he found himself having to navigate his own work-life balance.

It’s the pain of grazing.

He wanted to continue working flexibly as he had in the U.S.—taking his child to school before starting work, then focusing on emails and customers, taking time out for lunch, more customer time, then breaking to spend late afternoon and dinnertime with his family before finishing off work in the evening.

“This,” stresses Fily, who was born in France, “is not the French way.”

But instead of feeling guilty or worrying that he wasn’t adhering regional norms around work style, Fily knew he was productive and balanced, because he was using his own employee dashboard to gain these insights.

“I can see how I am doing. I can measure and see that I am going in the direction that I want. To me, that’s the goal—to see how you are doing and be able to shift how you work if you want.”

Getting there together

Employees and companies are poised to shift the culture of work because we’ve moved from acceptance—we understand technology is all-encompassing and work has fundamentally changed—to being ready for action. We can now do something about our state of near-constant connection, harnessing technology to help us unplug from work in intentional ways that are supported by collective norms.

“We have talked to a bunch of people, customers, employees, leaders, and analyzed data to find out the most common roots of this problem: people have too many meetings, they don’t block time, they feel the need to make up their lost focus time at home. During their personal time they are stressed out and unhappy. They get interrupted, by system notifications and people notifications. And there’s human psychology: some people cannot help responding to everything as it comes,” says Kalyan Nanduru, principal product manager for MyAnalytics.

But even those of us “beyond help” who think we might just be addicted to the ding of a notification can change. Organizations can look deeply at data to figure out what works and then replicate it; employees can team up to nurture a culture and each other in ways that honor the whole person and a healthy work-life continuum.

“People coming to work are just trying to get things done. I know, for example, that I cannot fix things like meeting culture on my own. If I want to stay offline in my personal time but my manager or teammates keep distracting me, I can’t,” Nanduru says.

“We have to build a system where we know if that’s happening across an organization. Then we can all work on it together.”

Unplugging is not tricking yourself. It’s not promising to stay in the moment but then constantly glancing at your inbox just to check in, so you don’t fall behind, because everyone else is doing it. Unplugging is a partnership on a journey toward the new way of working, and a key component of both personal happiness and workplace culture.

The ultimate vision could one day soon look like this: all of us spread out across parks and gyms and movie theaters and dinner tables and grocery stores and beaches focused wholly on our personal time, none of us contending with anticipatory stress because we’ve been empowered to solve for it. Then, when we’re all back at our jobs, we’re focused on the work that matters most, collaborating smartly, functioning effectively.

The two halves of a healthy whole.